USCOM in the Emergency Department.

Rapid evaluation of hemodynamics is carried out in every emergency department in the world every single day. In the main however, this usually consists of looking at some general parameters such as blood pressure, pulse rate and perhaps oxygen saturation. Some clinical evaluation of perfusion may also be made, but how much better would it be if we knew exactly what the hemodynamics were doing. Because of the non-invasive nature of the USCOM, and the speed with which such data can be acquired, the USCOM is beautifully suited to the emergency environment. Let's take a look of a couple of cases that presented in our own emergency department and see just how the USCOM improves clinical management of the patient.

Clinical Case 1.

Male, 68 years old, 76kg. Acute onset of severe central chest pain and dyspnoea 40 minutes prior to admission. He had a past history of hypertension and angina. ECG shows ST elevation antero-laterally.

Observations: BP 96/53, pulse 108, Resp Rate 32, JVP clinically elevated.

SpO2 86% on 10 l/min O2. He was confused and agitated. Arterial gas analysis showed PaO2 52, PaCO2 28, pH 7.18, Lactate 18. CXR showed florid changes of pulmonary oedema bilaterally.

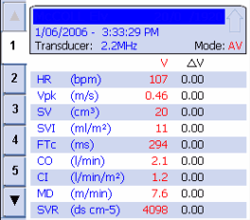

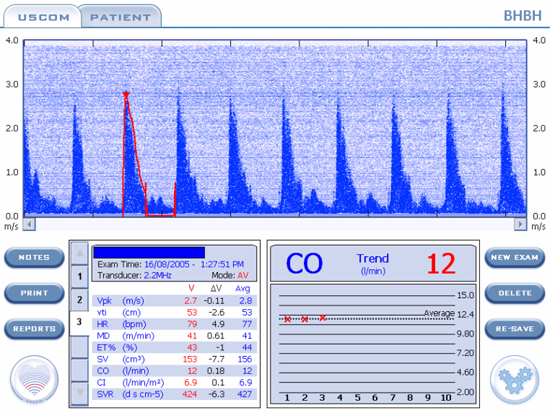

This is the USCOM data screen. What can you see?

The most obvious finding here is that his cardiac output and cardiac index are both low. The minimum cardiac index we should look for in a patient is 2.4 l/min/m2. Clearly this patient comes nowhere near this. His stroke volume is low, his peak velocity is low, and his SVR is markedly raised. What's going on here?

His myocardium is incapable of producing an adequate stroke volume, and the low peak velocity suggests a very low myocardial contractility (inotropy) status. His peripheral circulation is responding to the low cardiac output by vasoconstriction, giving him a high SVR of nearly four times normal. As a result of this, the blood flow in his aorta is much slower than normal as indicated by his MD (the normal is 14-22 metres/minute). It's clear that this is a hypodynamic circulation.

But what is actually killing the patient? On a superficial level we might answer "cardiogenic shock" but what do we actually mean by this? We know that shock is “any haemodynamic derangement leading to inadequate perfusion and oxygenation of the tissues”. So what is this patient’s oxygen delivery? We know from "The USCOM and Hemodynamics" how to calculate this. When we plug in the numbers in this case we find that the oxygen delivery is only 372ml/min. For a man of his size, a figure of even twice this value would be only just about enough.

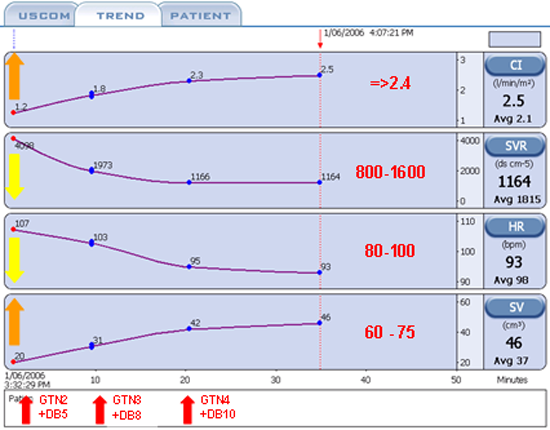

This is the trend screen of the USCOM over the next 35 minutes. The figures in red on the right hand side have been added to show the normal values that we should aim for in a man of this age and size. In effect, these are our early goals in therapy. His cardiac index at 1.2 must be increased; his SVR at over 4,000 must be reduced; his heart rate should be reduced and his stroke volume needs to increase significantly. So how did we treat him?

GTN2 and DB5 refer to glyceryl trinitrate infusion at 2mcg/kg/min and dobutamine at 5mcg/kg/min. Why did we choose these agents? The USCOM shows that his cardiac output is inadequate and from clinical observation and from his chest X-ray it is clear that his preload is already very high. We need to off-load him urgently. Nitrates achieve this more rapidly than anything else. But why did we choose dobutamine? Well he needs one or other inotrope to increase his cardiac index, but in the presence of a low blood pressure many people would opt for dopamine or noradrenaline or even perhaps an adrenaline infusion, but the USCOM shows that this is not appropriate. His SVR is so high that we need to vasodilate his arterial tree (reduce his afterload) if we hope to increase his stroke volume, given that his myocardial contractility is low. The GTN will help a little but the most logical inotrope to use is dobutamine because of its vasodilator properties.

Repeat USCOM shows that his SVR, stroke volume, cardiac index and heart rate are all going in the right direction. The infusions are then increased to 3 and 8 mcg/kg/min. Again, repeat measurement shows that we are making good progress. Finally, the infusions are increased to 4 and 10 mcg/kg/min. Following this, we have achieved our early goal in terms of his overall hemodynamics.

As the time scale on the trend screen shows, the treatment of his cardiogenic shock was achieved in just 35 minutes and this was carried out in the Emergency Department. By the time the patient was transferred to the Coronary Care Unit his immediate problem had already been solved. The importance of diagnosing the haemodynamic problem and treating it appropriately and rapidly is obvious. His vital signs, laboratory results and radiology two hours post admission are interesting.

BP 108/64, pulse 74, SpO2 96% (on 4 l/min O2), CI = 2.8 l/min/m2,

SVR = 1082, SV = 66ml.

PaO2 = 93, PaCO2 = 35, pH = 7.38, Lactate = 1.6

His oxygen delivery is now 926ml/min, an increase of 249%!

Over the next few hours his pulmonary oedema resolved completely.

Coronary angiography showed triple vessel disease, not amenable to stenting. He subsequently underwent CABG x 3, on the 7th day after admission. He made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on the 21st day after presentation with no symptoms. At 6 month follow up he remained well with no angina.

Clinical Case 2.

24 year old female 58kg. Previously fit and well. Only medication is oral contraceptive pill. Brought in by ambulance as “collapse”. Patient very confused and little history available.

GCS 5-6, BP 73/42, pulse 80, Temp 38.3, SpO2 92% on 4 l/min O2, Resps 26, Sweaty++, Right calf and foot visibly swollen. CXR - unremarkable. ECG – sinus rhythm. Blood glucose 4.3mM/L.

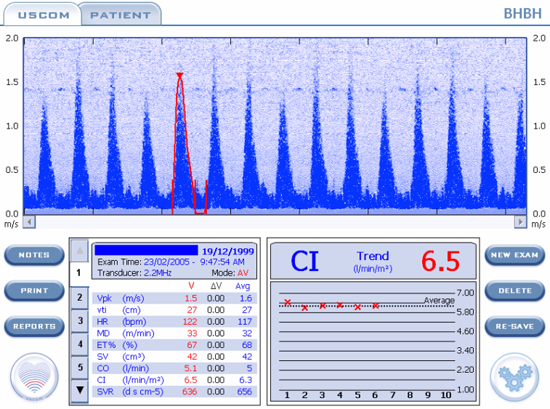

Initial diagnosis was right-sided DVT with pulmonary embolus. Here is her USCOM. What do you see?

This is indeed an odd pulmonary embolus! Her cardiac output is 12 l/min with a cardiac index of almost 7. It would be a very strange blood clot in the pulmonary artery that allowed such a large volume of blood to flow past it and yet rendered the patient prostrate! The Vpk shows that her myocardial contractility is excellent, her heart rate is not elevated, the MD shows that the circulation is hyperdynamic and she has a stroke volume of around 2.5 ml/kg. So what's going on here? The answer is immediately apparent when we look at SVR. At just 424, this is about one-third of normal. We are looking at peripheral vascular collapse with a hyperdynamic circulation and high cardiac output.

What is your diagnosis now?

Closer clinical examination revealed an 8 x 5cm patch of cellulitis on the upper inner right thigh with small ischaemic areas within. Inguinal lymphadenopathy was present on the right. The diagnosis must be septicaemia.

She was treated with iv antibiotics, iv fluids, and phenylephrine, an alpha-agonist (vasoconstrictor). Dopamine or noradrenaline would also be reasonably logical choices.

BP increased within 30 minutes to 105/60. She regained full consciousness and was able to report that the patch on her thigh had appeared one day earlier “like an insect bite”. It had increased in size overnight. She had intended to see her GP “later today after work” but had not felt well enough to go to work so went to bed instead. She woke up in ED!

Her temperature settled over 36 hours, vasopressor infusion was required for 18 hours. She needed 4L of fluid in the first 2 hours, but only 3 litres over the next 24 hours. She required 28-35% oxygen for 18 hours until PaO2 readings stabilised.

Subsequently (4th day) she required skin-grafting of a sloughing lesion of the right thigh for necrotising cellulitis. The infection was confirmed as streptococcus from wound swabs and the same organism was found in her blood cultures. She made a full recovery.

Clinical Case 3.

Female 5 years old, struck by car, multiple trauma.

Conscious, GCS 13. Clinically shocked. BP 65/?, Pulse 165, resps 46/min, SpO2 93% on 4L O2.

Her examination and radiographic findings were:

Fracture - Pelvis (inferior and superior pubic rami, left side)

Fracture - Left femur

Fracture - Right humerus

Fracture - Left radius and ulna

Fracture - 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th ribs right side

Scalp laceration, right parietal – 6cm, bleeding+

Lacerations / contusions to both thighs

Bruising over right upper abdomen

Abdomen tender and guarding

In severe pain

She was given 1L Hartmann’s at scene / during transfer. In ED, she was given N/Saline 1L, Gelofusine 500ml, and packed red cells (red cell concentrate) x 2, Morphine 4mg iv + further 1.5mg.

Her observations after 45 minutes were:

Pulse 124, BP (right thigh) 85/42, SpO2 = 96% (4 l/min O2)

The skin felt cool and she felt sweaty to the touch.

Is the patient adequately volume resuscitated?

Peak ejection velocity increases with fluid loading. The normal at 5 years is 1.3 – 1.4 m/s. 1.5-1.6 m/s indicates adequate to excessive fluid loading. It also suggests a vasodilated vascular tree, as vasoconstriction produces back pressure on the ventricle (a high afterload) which limits peak ejection velocity. Mean aortic flow velocity as indicated by the MD is increased above normal, indicating a hyperdynamic circulation. Again, this suggests excessive fluid loading and vasodilation. The normal stroke volume is 1.5-2ml/kg at this age. A child of this age would typically weigh around 18kg and an SV of 42ml suggests she is “well filled”.

The cardiac index is high and given the stroke volume, is more due to excessive heart rate. The SVR of 636 shows that the patient is vasodilated. This could well be due to the morphine that she has received as morphine is a potent vasodilator. Although the potential exists with these injuries for major blood loss to occur, in fact, the patient is now slightly hypervolaemic rather than hypovolaemic.

When the patient was catheterised, urine output exceeded 3ml/kg for the next few hours. Over the first 24 hours, only 750ml of crystalloid and 1 unit of red cell concentrate were needed to maintain normal hemodynamics and urine output. The haematocrit at 24 hours was 0.41 and Hb 142g/L. The right lung showed patchy contusion, but no major opacification on CXR. Supplemental oxygen at 2 l/min was required for 24 hours, but no ventilatory support.

The child made a full recovery.

It would be extremely easy in a case such as this to over estimate the blood and fluid requirements for the patient. Injuries such as these could lead to virtual exsanguination of the patient if they all produced their maximum possible blood loss. In fact, in this case, the blood loss from the injuries was very much less than one might normally expect. Excessive fluid loading in this patient could well have led to significant pulmonary compromise with respiratory distress syndrome and the need for ventilatory support. Using the USCOM to guide fluid therapy may well have prevented this eventuality, we’ll never know, but it certainly made the clinical judgment of fluid requirements very much easier. Had the blood loss been on a more massive scale, then we could have used the USCOM to detect the hypodynamic circulation due to underfilling and responded accordingly. No more guesswork!

|