The USCOM in Intensive and Coronary Care.

Just imagine that you had been admitted to Coronary Care having just had a heart attack. Is there any one of you who wouldn’t want to know your hemodynamics? You might think that would be enough of an answer, but just to labour the point, try this case.

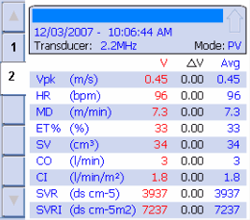

A 47 year old male office manager is admitted to CCU from the ED with a confirmed ST-elevation myocardial infarction. He was hypotensive on admission to CCU with a BP of 96/52 and was commenced on noradrenaline at 100ng/kg/min. Here are his hemodynamics 20 minutes later. His BP had risen to 108/68.

What do you see? Are you happy with his hemodynamics? How would you alter this patient’s management, and what drugs would you use to achieve improved hemodynamics? What would you like his parameters to be?

The Intensive Care Unit.

From all that has been said in this booklet and in the first booklet “The USCOM and Hemodynamics” you probably think that just about all the features of the USCOM have been described already. Well yes and no!

I have repeatedly stressed the importance of looking at the circulatory system as a whole rather than individual parameters. In intensive care, we have to look at the patient as a whole and interpret the USCOM readings accordingly. Let’s pick a typical example of the interaction between ventilation and circulation.

The patient is a 67 year old female with pneumococcal pneumonia leading to bibasal consolidation.

On the left we see her hemodynamics when she was on SIMV with an inspired oxygen concentration of 70%. She was on PEEP at 5cm H2O. Her SpO2 was just 85% with a PaO2 of 58mmHg. Her PaCO2 was normal.

Would you increase her FiO2, increase her PEEP, or leave well enough alone? I think that just about everybody would opt for increasing PEEP from 5 to 10 or even 15cm H2O. The clever doctors will tell you that you titrate PEEP to achieve the optimum result. Unfortunately, they seldom spell out what exactly they mean by “optimum” or so-called “best PEEP”. Do you take an increased SpO2 as a good result? Do you measure the arterial gases and assume an increased PaO2 is a good outcome? Many intensivists do just that.

The right hand panel shows what happened when her PEEP was increased to 12cm H2O. Her saturation certainly improved. Unfortunately, this is not the only thing that matters. Whilst the SpO2 has risen by a little over 10%, (with a commensurate rise in her PaO2), the cardiac output has gone down by over 35%. The net result of this is that her oxygen delivery, DO2, has fallen by 20%. The pulse oximeter may say she’s better on the higher PEEP, but the USCOM tells the real story. The search for “best PEEP” is a great deal easier when you have appropriate tools to measure the response to your manipulations, especially now that the USCOM can give you DpO2 directly.

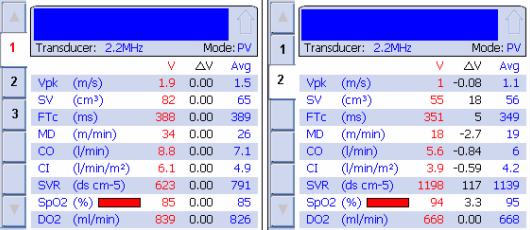

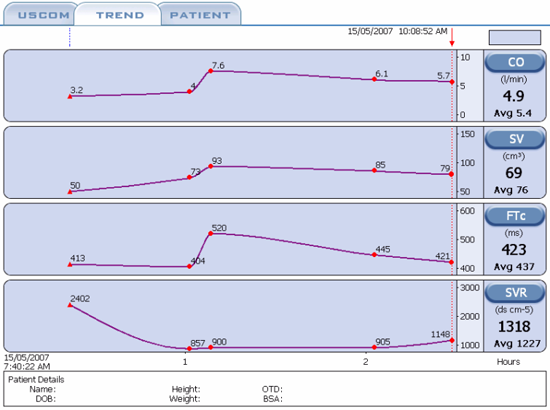

The next case is a 62 year old man admitted to ICU following an emergency laparotomy for a strangulated inguinal hernia. At surgery approximately 1.5 metres of small bowel was removed as being of doubtful viability. His BP during the surgery had been consistently low averaging 85/50. Towards the end of surgery he was commenced on a noradrenaline infusion which increased his BP to 105/60. The presumptive diagnosis was that he had developed septicaemia. Here is his trend display.

Looking at his admission figures (first reading), do you agree with the diagnosis? What would you do instead?

In fact, the hemodynamics suggest that he is volume depleted, with a low SV and CO and a high SVR indicating excessive vasoconstriction. He has a moderately low FTc in spite of the vasoconstrictive effects of the noradrenaline. He was treated by gradual withdrawal of the noradrenaline with simultaneous volume expansion. At the 1 hour marker his noradrenaline was discontinued and 500mls of Hartmann’s solution infused rapidly. Although the USCOM showed that this bolus of fluid was largely equilibrated after one hour, his hemodynamics remained adequate and maintenance fluid only was sufficient to keep his cardiovascular parameters in the normal range.

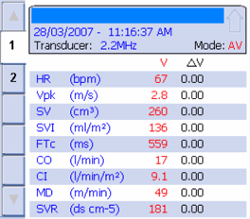

In this final case, a 46 years old male, 118kg, type 1 diabetic was admitted to ICU with hypotension (85/40) following incision and drainage of a large axillary abscess under general anaesthesia. His ECG showed ST depression in the anterior and lateral chest leads, with a normal heart rate and normal conduction. Here are his admission hemodynamics. What is your diagnosis? How would you treat him?

With a CO of 18 l/min it is not surprising that he has evidence of myocardial ischaemia, especially with a diastolic BP of only 40. This is the pressure that perfuses his coronary arteries. His CI is more than 3 times normal yet he is still hypotensive. The FTc of 559 shows that he is well pre-loaded, indeed it suggests overloaded, so what is the problem? The MD shows that this is a very hyperdynamic circulation. The SVR makes this a no brainer! He is septic with peripheral vascular collapse. Although his heart is ejecting more than 3 times the normal CO, his SVR is only one-sixth of normal. From BP = CO x SVR, even this high CO cannot maintain the BP in the face of such vasodilation.

As regards treatment, whilst your first thought might be to just use a vasoconstrictor (pressor) agent, you must always beware of underlying myocardial depression. Whilst the patient is this vasodilated, there may not seem to be any evidence of this, but as the SVR rises the true state of myocardial function may become apparent. Consider dopamine or noradrenaline as the situation unfolds, and repeat the USCOM regularly!

As a final thought, why do you think his heart rate is only 67? He is a type 1 diabetic so it is unlikely to be due to a ß-blocker. What else could be going on?

|