Preload and Stroke Volume.

To understand this we need to look at the classic work of Frank and Starling, who looked at the stroke volume that resulted from any given degree of ventricular preloading.

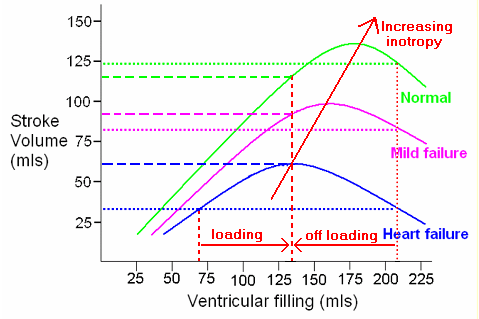

The ventricular preload is essentially the volume of blood in the ventricle immediately prior to systole. They found that very distinct patterns emerge for the normal heart and the failing heart. The diagram above shows three different preloadings, 1ml/kg, 2ml/kg and 3ml/kg, and three levels of heart function, normal, mild failure and established ventricular failure. If we look at the failing heart, we find that the stroke volume is critically dependent upon the preload. With an optimal preload of 2ml/kg the output stroke volume is double that of the underloaded heart at 1ml/kg or the overloaded heart at 3ml/kg. In effect, we can double the stroke volume simply by correcting the preload from the under or overloaded state to an optimum value. If the preload is too low, as in haemorrhage or dehydration, then this will respond to volume expansion, or loading. If the preload is too high, as may occur in congestive cardiac failure, then reducing it by using vasodilators or frusemide can produce a dramatic improvement in stroke volume and cardiac output.

Stroke volume is therefore critically dependent on the volume of blood in the left ventricle at the end of diastole, the end diastolic volume or LVEDV (or RVEDV in the case of the right ventricle). There is no easy way to measure this, but from the Frank Starling curve we know that the optimum value of end diastolic volume must be when the stroke volume is maximal. If we think the patient may be hypovolaemic or underfilled then try volume expansion, perhaps 250 to 500 mls of intravenous fluid. If we're sure that the patient is overloaded, then try a vasodilator such as GTN. Did the stroke volume and cardiac output increase as we expected? If the answer is yes, then we are going the right way. Carry on doing what you're doing until the stroke volume reaches a peak and just begins to fall. You have now found the peak of the Frank Starling curve.

But what if we don't know if the ventricular preload is too high or too low? Do you try giving fluid and risk further overloading of an already overloaded ventricle? What if the ventricle is not yet optimally loaded but we give frusemide or vasodilators, will we make things worse? Primum non nocere, first do no harm.

Can the USCOM tell us which way to go in this situation? The answer is yes, and very easily. First, with the patient lying supine, measure the stroke volume. Then elevate the legs (not tip the whole patient, just lift the legs). This will auto-transfuse a few hundred mls of blood into the central circulation. Did the SV increase or decrease? If the SV increased then the patient is under loaded. Simple volume expansion is called for. Did the SV fall? No problem, the ventricle is already overloaded. Put the legs down again, and this puts us back to where we started with no harm done. Now let's off-load the patient with a diuretic, vasodilator or whatever - just so long as it reduces the preload. How much vasodilation/diuretic do we need? Well, that dose that maximises the stroke volume - simple titration of preload against stroke volume. We can repeat the leg raising test as often as we need to.

|